A Unique Threat to Human Resource Development: An Unprecedented Pandemic

Madhu Bala Nath

The world is experiencing an unforeseen, unprecedented pandemic of an intensity that has paled ALL other epidemics that have taken the globe by storm over the last century. Why? Because of its mutating nature which makes vaccine development a challenge, its sudden and quick progression into death or fractured health which has implications on mortality and morbidity of the world’s labour force, its ability to infect and transmit to people unless a social distance is maintained, its ability to stay alive on surfaces for days, its ability to transmit from one body to another even with a low viral load. It has unique challenges in resource poor settings where infrastructural challenges fall weak to its potency. Its impact on health systems is crippling as survival is dependent on the existence and functioning of intensive care facilities and availability of a robust health worker force. Above all, its onslaught requires a lock down and consequent crippling of erstwhile vibrant and robust economies. It brings lives and livelihoods suddenly and with hardly any warning to a screeching halt.

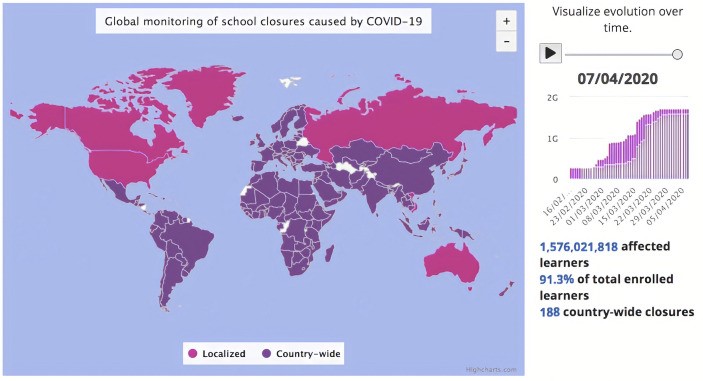

COVID-19 has affected all levels of the education system, from pre-school to tertiary education. Over 100 countries including India, have imposed a nationwide closure of educational facilities. UNESCO estimates that globally close to 900 million learners have been affected by the closure of educational institutions. The map below shows that the closure of schools in India has been countrywide. It is interesting to note that in countries that are resource rich and where the citizen’s entitlements have been honoured, the closure of schools has been localised.

How

are entitlements honoured in these resource rich countries?

Entitlements are seen as fundamental rights and so governments in

these countries hold themselves accountable to their citizens to honor

these rights. So if livelihood is an entitlement, then the governments

engage in employment creation and make sure that their policies

prevent a jobless growth. Similarly, where the right to health is

respected governments are accountable to ensure that health

infrastructure is adequate to serve the health needs of all its

citizens even in such times of crisis. Coming to education, the right

to education binds governments to ensure that education services reach

every doorstep so that human potential is nurtured for the nation’s

growth and personal liberation.

How

are entitlements honoured in these resource rich countries?

Entitlements are seen as fundamental rights and so governments in

these countries hold themselves accountable to their citizens to honor

these rights. So if livelihood is an entitlement, then the governments

engage in employment creation and make sure that their policies

prevent a jobless growth. Similarly, where the right to health is

respected governments are accountable to ensure that health

infrastructure is adequate to serve the health needs of all its

citizens even in such times of crisis. Coming to education, the right

to education binds governments to ensure that education services reach

every doorstep so that human potential is nurtured for the nation’s

growth and personal liberation.

Unfortunately, these entitlements whereas enshrined in our fundamental rights have not translated into compelling policies and programmes that could withstand the adversity that COVID threw the nation into. As the right to livelihood and the right to health stood ignored by a slowing economy and crumbling health infrastructure, the right to education also fell between the cracks. In India, COVID-19 has had an impact whereby schools are closed and so are no longer able to provide free school meals for children from low-income families leading to social isolation and school dropout rates. It has also had a significant impact on childcare costs for families with young children. Additionally, there exists a wide disparity amongst populations with a higher income who are able to access technology that can ensure education continues digitally during lockdowns. A recent report produced by NDTV highlighted how families in Himachal are unable to afford the costs of on line learning, and in Ladakh there are large areas where there is no connectivity because of terrain issues or issues relating to threats of external aggression. In many such locales children remain deprived of educational attainment.

Human Development – A Reversal ?

The UNDP human development reports launched in 1990 had very successfully moved the global discourse on development from economic indices to a few other indices that captured human well-being like life expectancy and literacy rates besides per capita incomes. These indices captured the progress of nations on the human development index. Today the COVID epidemic has put all these indicators under huge stress. Rising unemployment figures are putting per capita figures under huge stress, rising numbers of deaths of young and old arising out of COVID or its related adversities like hunger, unmet need for health services, are putting the life expectancy indicator under stress and the back migration and consequent pulling out of children from schools is a clear assault on the indicator of school enrolment rates. The implications of this state of affairs is already pointing towards a reversal in human development. With so many children out of schools and no assurance of their being able to access newer forms of education, creation of human potential to create a strong nation is under stress. it is also ringing the bell of intergenerational poverty that could create long term deprivations and dependencies in the lives of large numbers of our populace. It is time we sit up and take stock. It needs to be mentioned here that 65% of India’s population is under 35. It is our demographic dividend and we need to make sure that we preserve and grow its potential.

The right to livelihood, the right to health and the right to education are fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian constitution, they are entitlements but are they being honoured?

This state of affairs has repercussions for young girls. Findings from a sample of 1000 households in Andhra Pradesh found that parents were more willing to invest in private school fees and extra tuition fees for their sons than for their daughters, although the outlay for uniforms, books and transport was equal. Over the last 3 months millions of girls and boys have been pulled out of school. On line classes remain in the domain of the “haves” not the “have nots.” As more and more women in rural India seize whatever benefit they can get from MNREGA, in the absence of affordable child care options, more daughters than sons will be expected to shoulder additional responsibilities usually at the expense of their education. This mother substitute effect could get more pronounced in poor households.

According to Volger, young people’s time use and the extent to which they can shape decisions about how their time is allocated between education, work and leisure has a significant impact on their material, relational and subjective well being. Existing evidence suggests that time allocation patterns are highly gendered especially in impoverished households. Although there are important context variations, overall research findings point to girls’ greater involvement in domestic and care work activities and lower levels of participation in schooling and leisure.Covid could

could see more sickness in families. This situation will place a greater care burden on girls rather than boys. Research in Latin America especially Peru as well as in Indonesia has shown that the kind of burden that a young girl bears in a household battling with sickness varies depending on whether a child or an adult is sick in the house. Teenage daughters were significantly more likely to increase participation in household care activities and this would correspondingly decrease their participation in market activities and/or would lead to their dropping out of school. In the case of adult illness girls tended to compensate for the loss in family income by increasing their participation in income generating activities. Interestingly the researchers found no effect of this sickness in the time use of boys.

The number of resource poor households as a result of months of lockdown as well as the high unemployment created by a negative income growth are already facing deprivations like food shortages, inadequate shelter, no resources for consumption for survival. This social practice of child fostering or confiage is common in many parts of India especially in West Bengal, Jharkhand, Tripura, Chhattisgarh. Child domestic workers often work in the house of a relative, acquaintance or even a stranger where they have been sent by their parents at an age of as young as 5 years. According to a report published by Human Rights Watch in 2006, child domestic workers frequently find that even food is wielded as a tool of power by the employers with many girls going desperately hungry on a regular basis. Some girls reported being so hungry that they engaged in sex for money. If the host family treats the girl well, sends her to school and allows her to be in contact with her parents she might have a better future than in her own deprived family. However many child domestic workers are abused, sexually and emotionally and they have no way to seek redress as the abuse is hidden from public scrutiny. This social practice may increase because of increasing deprivations that families especially migrants and jobless families and will need attention.

This possible scenario has the potential of reversing the gains made in the reduction of child marriages over the last decade. School enrolment rates have already dropped, school dropout rates are rising, but the ray of hope is that the issues are being diagnosed and projected by researchers and activists. Policy and programmatic responses now need to follow. I write this with hope and eager anticipation of a new dawn.

—00—

If you can find a path with no obstacles, it probably doesn’t lead anywhere

- Frank A. Clark